Congratulations to our 2020 AP Students on Exam Results

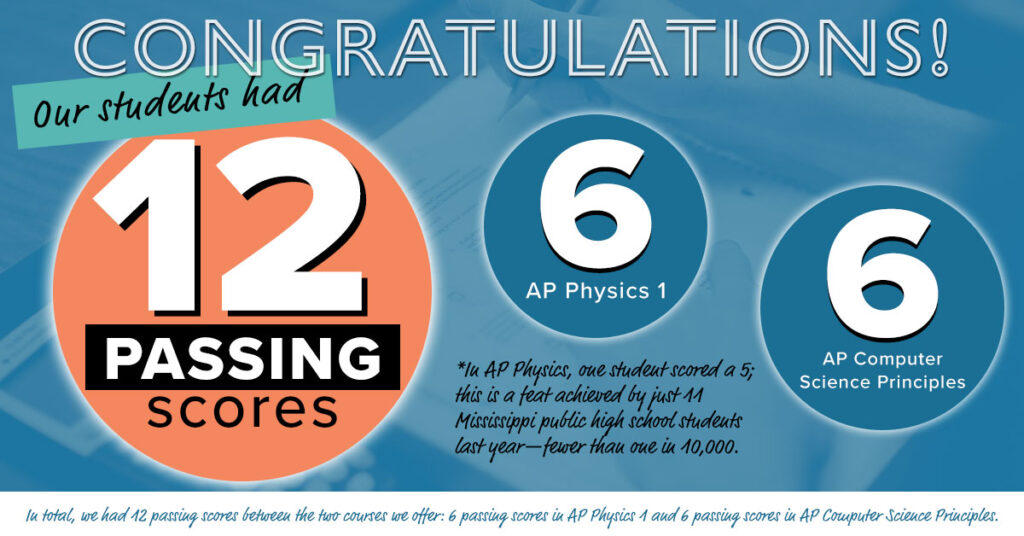

Congratulations to our 2020 AP Students! This year, we had 12 passing scores: 6 passing scores in AP Physics 1 and 6 passing scores in AP Computer Science Principles.

We recently received scores our students earned on the Advanced Placement (AP) Physics 1 exam administered in May and June, and the AP Computer Science Principles (CSP) performance tasks submitted in May. We are pleased to report that the news is good.

We recently received scores our students earned on the Advanced Placement (AP) Physics 1 exam administered in May and June, and the AP Computer Science Principles (CSP) performance tasks submitted in May. We are pleased to report that the news is good.

The most remarkable aspect of the scores is, of course, that they were earned at all—our students had to overcome unprecedented challenges even to complete their courses.

Because of the pandemic, each of our schools physically closed in early March, thus requiring our students to continue working outside a conventional classroom structure for two to three months before the AP Physics exams were administered and the AP Computer Science submissions were made.

We provided our students with substantial support, including daily instructional sessions from March until May. Yet for our students to persist amidst a global pandemic, closed school buildings, limited internet access, and pervasive uncertainty required extraordinary commitment.

Even taking their exams or submitting their performance tasks presented major challenges for our students, who had to do so remotely by computer, phone, or even through photos of handwritten pages. Also, technical problems plagued AP exam administration nationally. As a result, numerous students completed their tests, only to be unable to submit their answers, and thus had to take makeup exams weeks later, which required them to persist further in their studies while schools remained closed.

What our students achieved was not just commendable, it was heroic.

Despite those challenges, the AP scores are heartening.

The number of qualifying scores—that is, the score (typically 3 on a scale of 5) required to earn college credit for a subject—was up sharply from prior years. Moreover, improvement was evident in each part of the state we serve—the Delta, northeast, and central Mississippi.

Overall, the percentage of our students who earned a qualifying score in AP Computer Science Principles was just 4.6% below the statewide rate—notwithstanding that this was the first year we offered the course, and our schools had very different profiles than those typical of other schools that offered the course. In one of our schools, every Computer Science student earned a qualifying score.

On the AP Physics 1 exam—which has lowest average score nationally of any of the 38 AP subjects and is a challenge that just 0.2% of Mississippi public high school students even attempted last year—we had significantly more students score among higher quartiles of that elite group. Also, for the first time, one of our students earned the highest possible score, a feat achieved by just 11 Mississippi public high school students last year—fewer than one in 10,000.

Although we clearly made progress, we very much acknowledge that the AP scores also demonstrate that we just as clearly have a long way to go.

We also acknowledge the limitations of AP exams, which, if used properly, can be an important tool, but are not, and should not be, our focus.

Our initiative provides promising high school students from rural Mississippi communities access to advanced STEM courses they need to achieve their full potential, but which their schools had not previously offered. We do so to promote learning, college preparedness, and, ultimately, career success.

AP exams can help advance progress toward those goals by promoting rigor, providing accountability, and helping assess the efficacy of our work, but AP scores are not the goal themselves.

Like our students, we are not deterred by challenges—we embrace them.

Although our commitment to serve communities that have the greatest needs tends to lower our average exam scores, that is a tradeoff we cheerfully accept. Thus, we seek to serve schools where we may make the most positive impact, and whose students otherwise would be denied opportunities to excel—in the 40 counties with the nation’s highest poverty rates, our schools are the only public schools in any state that offer AP Physics 1, and in the 25 counties with the nation’s highest child poverty rates, our schools are the only ones that offer AP CSP.

Despite those considerations, we still expect to be judged on the progress we make over time.

Performance metrics rely on various data points to permit rigorous analysis—not just how students perform on an exam, but also how that performance compares to various baselines, how their performance compares to similar control groups, and how, over time, their work translates into longitudinal success in college persistence, graduation rates, grades, and major selections.

The performance metric that our program has utilized to date that presents the most such data points is the Force Concepts Inventory (FCI), an exam for introductory college and advanced high school classes that is widely used to “assess students’ understanding of the most basic concepts in Newtonian physics using everyday language and common-sense distractors.” The FCI establishes an initial baseline and precisely quantifies progress from that baseline on a scale of 1-100. In the last two years, we administered the FCI to students in our Summer Program, and the results showed that students made considerable progress over the course of both programs.

By comparison, AP scores present methodological limitations. Unlike the FCI, AP scores do not note where students start in their substantive knowledge base, but only where they finish—thus, they are a measure only of where students are at a single point in time, not of the progress they have made. Also, AP scores, which are on a scale of 1-5, present results within relatively broad bands, and not with precision. Small sample sizes also skew scores. Furthermore, ample data indicates that students who take AP Physics are vastly more likely to come from relatively affluent areas and attend schools with considerable resources, so identifying appropriate control groups against which to measure progress is problematic.

For all those reasons, we do not view AP scores as the definitive metric of our students’ success. To the contrary, the most important measure of our students’ success will be the longitudinal outcomes that will not be evident for many years.

Neither those outcomes, nor the factors that contribute most meaningfully to long-term success, are readily quantifiable. Instead, our students’ futures will be most determined by traits they already have demonstrated in abundance, particularly in recent months, and which our initiative seeks to develop further—perseverance, resolve, enthusiasm, and the ability to identify a worthy goal and work collaboratively and cordially, even joyfully, with others to achieve it.

Tag:advanced stem, AP Test